The Stage is Set

By Jack Schnedler

It hit like a tornado, with a whirlwind impact both sudden and shattering.

The desegregation storm of September 1957 ripped into Little Rock's self-image of Southern racial moderation and plunged the city into turmoil for nearly two years. The Central High crisis became the most defining chapter in Little Rock's history.

Feelings about the issue ran high nationally on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. When a Sept. 10, 1957, performance of South Pacific in a New York City suburb reached the line where Nellie Forbush says she is "a little girl from Little Rock,'' the audience booed so loudly that the show had to be halted. When Gov. Orval E. Faubus' presence was announced at the Sept. 21 Texas-Georgia football game in Atlanta, the 33,000 fans gave him a standing ovation.

Decades later, the desegregation crisis is part of the history books, lying beyond active recollection for most Arkansans. But it also remains a current event, because some of the participants are still alive and some of the scars have yet to heal. How to integrate schools equitably continues to bedevil officials and parents here as elsewhere.

The seeds of the Little Rock confrontation were sown in May 1954 by one of the century's most important and controversial U.S. Supreme Court decisions, Brown vs. Board of Education. The following timeline traces developments on the 39-month path from Brown to Central and the two years after the crisis.

1954

May 17: The U.S. Supreme Court rules unanimously in Brown vs. Board of Education that state laws mandating public school segregation are unconstitutional under the equal-protection clause of the 14th Amendment. The high court rejects the "separate but equal'' doctrine in force since its Plessy vs. Ferguson ruling of 1896, declaring that segregated schools "are inherently unequal.'' May 17: The U.S. Supreme Court rules unanimously in Brown vs. Board of Education that state laws mandating public school segregation are unconstitutional under the equal-protection clause of the 14th Amendment. The high court rejects the "separate but equal'' doctrine in force since its Plessy vs. Ferguson ruling of 1896, declaring that segregated schools "are inherently unequal.''

May 18: Gov. Francis Cherry says Arkansas will "comply with the requirements'' of the Supreme Court desegregation ruling.

May 22: The school boards in Fayetteville and Sheridan announce that their systems will desegregate in the fall. The Sheridan board rescinds its decision the next day in the face of public outcry.

June 5: Gubernatorial candidate Orval E. Faubus, a former state highway commissioner and the postmaster at Huntsville, pledges in his first campaign statement on school integration "that the rights of all will be protected but that the problem of desegregation will be solved on the local level, with state authorities standing ready to assist in every way possible.''

Aug. 10: Faubus wins the Democratic nomination for governor by defeating incumbent Cherry after a heated primary runoff campaign, 191,328 to 184,509.

Aug. 23: Public schools in Charleston, Ark., admit 11 black students, making that Franklin County community the first in the former Confederacy's 11 states to end school segregation. Charleston's school superintendent waits until Sept. 14 to disclose the desegregation to the news media.

Sept. 4: Arch Ford, Arkansas commissioner of education, reminds 14 school districts that have submitted petitions to desegregate: "There is a state law against integration. ... The State Board suggests local boards comply with state law in the absence of any decree from the U.S. court.''

Sept. 7: Fayetteville High School enrolls nine blacks along with 500 white students, following Charleston as the second desegregated system in Arkansas and the Old South.

Gradual school desegregation begins in several border states and the District of Columbia.

Oct. 6: Desegregation in Baltimore and Washington, D.C., high schools is upheld by local officials in the face of anti-black "strikes'' by about 2,000 white students in each city.

Nov. 2: Faubus wins his first term as Arkansas governor by capturing 62 percent of the vote over Republican Pratt Remmel.

Louisiana voters approve a state constitutional amendment to permit segregated education under the state's "police powers.''

Nov. 15: Arkansas and six other Southern states plus the District of Columbia file briefs urging that the Supreme Court permit gradual application of its ruling against school segregation. Attorneys for black parent groups in four states petition the court to order total desegregation by September 1955 or September 1956.

Dec. 21: Mississippi voters approve by a 2-1 majority a state constitutional amendment to permit abolition of public schools if there proves to be no other way to avoid racial integration.

1955

April 13: U.S. Solicitor General Simon E. Sobeloff, representing the Eisenhower administration, tells a Supreme Court hearing that racial segregation of public schools should be halted gradually and with "moderation.''

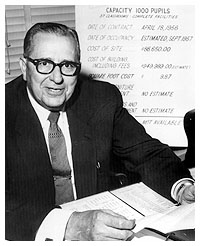

May 24: The Little Rock School Board and Superintendent Virgil T. Blossom disclose early details of their desegregation plan to comply with the Brown decision. Later known as the Blossom Plan, it is designed to phase in limited desegregation, starting with one high school in 1957 and gradually reaching down to the first grade by 1963. May 24: The Little Rock School Board and Superintendent Virgil T. Blossom disclose early details of their desegregation plan to comply with the Brown decision. Later known as the Blossom Plan, it is designed to phase in limited desegregation, starting with one high school in 1957 and gradually reaching down to the first grade by 1963.

May 31: Public school segregation must be ended "with all deliberate speed,'' the Supreme Court rules unanimously in what becomes known as the Brown II decision. Written by Chief Justice Earl Warren, it sets no deadlines.

July 11: Twenty-five blacks enroll peacefully amid 1,000 white students in Hoxie, the third Arkansas school system to desegregate and the first in an area of the state with a substantial black population.

July 14: North Little Rock's school board adopts a plan to desegregate at the high school level in the fall of 1957.

Aug. 4: Dr. William G. Cooper Jr., president of the Little Rock School Board, sends a letter informing Daisy Bates, president of the Arkansas Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, that there will be no integration of students before September 1957.

Aug. 20: Mounting white opposition to integration in Hoxie, following a story in Life magazine, leads the local board to close its schools.

Oct. 24: Hoxie schools reopen after a federal court bars segregationists from preventing the admission of blacks. Widespread white absenteeism is reported.

Nov. 7: The U.S. Supreme Court, in two unanimous decisions, bans racial segregation in publicly financed parks, playgrounds and golf courses. Nov. 7: The U.S. Supreme Court, in two unanimous decisions, bans racial segregation in publicly financed parks, playgrounds and golf courses.

Dec. 5: Blacks begin boycotting the municipal bus line in Montgomery, Ala., after Rosa Parks is fined $14 for refusing to give up her seat and move to the rear as law required when white passengers entered the bus. Martin Luther King Jr., a 26-year-old minister, becomes leader of the protests.

1956

Jan. 23: Twenty-seven black students, under the aegis of the NAACP's Bates, are turned away when they try to enroll for the spring semester at Central High, Tech High, Forest Heights Junior High and Forest Park Elementary School. Their enrollment is refused on the grounds that school authorities haven't yet had time to make plans.

Jan 28: Gov. Faubus reports that "85 percent of all the people'' in Arkansas opposed school desegregation in a statewide poll he commissioned in November.

Feb. 8: A federal lawsuit is filed in Little Rock by 12 black parents on behalf of 33 students to compel the School Board to desegregate the city's schools without further delay. NAACP lawyers in the suit include Thurgood Marshall, a future U.S. Supreme Court justice.

March 11: All eight members of Arkansas' congressional delegation are among the 19 U.S. senators and 81 U.S. representatives to sign the Southern Manifesto. The document denounces the Supreme Court's 1954 Brown decision and pledges to use "all lawful means'' to have it reversed. Arkansas signers include Sens. John L. McClellan and J. William Fulbright and Reps. Wilbur D. Mills, Brooks Hays, James W. Trimble, Oren Harris, E.C. Gathings and W.F. Norell.

March 18: Pro-segregation candidates win the school board election in Hoxie.

April 26: Little Rock integrates its municipal bus system, three days after the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed segregation on intrastate buses. No trouble is reported.

April 30: Former State Sen. James D. "Jim'' Johnson of Crossett announces his Democratic candidacy for governor at a rally in Little Rock, after Hoxie segregationist leader Herbert Brewer comes to the stage and "suggests'' that he run. Johnson attacks Faubus' "do-nothing stand on segregation.''

May 9: Little Rock's new Horace Mann High School, a segregated facility for black students, opens at McAlmont Street and Roosevelt Road. Superintendent Blossom calls the $925,000 school "the very best this community could offer.'' May 9: Little Rock's new Horace Mann High School, a segregated facility for black students, opens at McAlmont Street and Roosevelt Road. Superintendent Blossom calls the $925,000 school "the very best this community could offer.''

July 11: Faubus tells a campaign rally in Marianna: "No school district will be forced to mix the races as long as I am governor of Arkansas.''

July 23: Candidate Johnson labels Faubus "a race-mixer.''

July 31: Faubus wins the Democratic primary without a runoff, garnering 180,760 votes to 83,856 for Johnson.

Aug. 28: U.S. District Judge John E. Miller upholds the Little Rock School Board's gradual desegregation plan in the case brought by black parents. "This court shall not substitute its own judgment'' for the School Board's, Miller writes.

Aug. 31: Texas Gov. Allan Shivers sends Texas Rangers to Mansfield to preserve order after segregationist demonstrators prevent eight black students from enrolling. Four days later, the blacks give up attempts to go to classes.

Sept. 25: Democratic presidential candidate Adlai E. Stevenson, introduced by Faubus at a rally in Little Rock's MacArthur Park, says the Supreme Court's school desegregation ruling was right and asks Arkansans for peaceful compliance.

Nov. 6: Faubus is re-elected governor with 80 percent of the vote over Republican Roy Mitchell.

Voters statewide approve three segregation measures. Initiated Act 2, which authorizes school boards to assign pupils to preserve segregation, gets 73 percent of the vote. The Arkansas Resolution and Act of Interposition, which puts the state on record as opposing racial mixing in schools, gets 60 percent. Constitutional Amendment 44, which propounds nullification of the Supreme Court's Brown rulings by interposing the sovereignty of the state, gets 56 percent.

Little Rock voters adopt a new city manager form of government by a 2-1 majority, leaving Mayor Woodrow Wilson Mann as a lame duck.

Dec. 20: Buses are integrated in Montgomery, Ala., under a federal injunction after a Supreme Court ruling. Blacks end their boycott of more than a year.

1957

Feb. 26: Faubus signs into law four segregation bills passed by the Arkansas Legislature. The laws establish the Arkansas Sovereignty Commission to make anti-integration investigations; authorize parents to refuse to send their children to desegregated schools; require organizations such as the NAACP to disclose membership and financial data; and allow the use of school district funds to hire lawyers and pay other legal costs of opposing desegregation suits.

April 29: A federal appellate court upholds the previous August's District Court approval of the Little Rock School Board's gradual desegregation plan. Expressing his pleasure with the decision, Superintendent Blossom says Hall High School, being built at 6700 H St., will open on schedule in September.

April 30: The pro-segregation Capital Citizens Council of Little Rock appeals to Faubus in a letter from its president, Robert E. Brown, to "order the two races to attend their own schools'' in the fall.

June 22: The North Little Rock School Board announces that 28 black seniors will be eligible to enter previously segregated North Little Rock Senior High in September.

June 25: The School Board in Fort Smith votes to desegregate classes in the fall.

June 27: Attorney Amis Guthridge and the Rev. Wesley Pruden, both opposed to integration, submit official requests to the Little Rock School Board posing a series of questions. Guthridge asks the board to act under a 1957 legislative act and provide separate schools for white and black children whose parents don't want them attending integrated schools. Among Pruden's questions: "If Negro children go to integrated schools, will they be permitted to attend school sponsored dances, and would the Negro boys be allowed to solicit the white girls for dances?''

June 30: A newspaper advertisement by the Capital Citizens Council calls on Faubus to require maintenance of school segregation, "since a sovereign state is immune to federal court orders and since the governor as head of the sovereign state is also immune to federal court orders.''

July 2: Ozark's School Board discloses its desegregation plans for the fall term.

July 27: The Little Rock School Board, answering the June 27 questions submitted by Guthridge and Pruden, says maintaining separate schools for whites or blacks who oppose integration would violate the U.S. Supreme Court ruling. It assures Pruden that the mingling of races at social events will be forbidden. The School Board also reveals that Central High will be the system's only school with integrated enrollment in September. All 700 students at the new Hall High will be white, it reports, and Mann High will remain all-black for the 1957-58 school year.

Aug. 16: Two black ministers file a federal suit seeking to have declared unconstitutional the four segregation bills passed by the Arkansas Legislature in February.

Aug. 17: A suit filed in state Chancery Court by Little Rock insurance man William F. "Billy'' Rector questions the validity of the Arkansas Resolution and Act of Interposition adopted by voters the previous November.

Aug. 19: A Chancery Court suit filed by Eva Wilbern for her 14-year-old daughter Kay asks that the Little Rock School Board allow white Central High students to transfer to a school that remains segregated.

Aug. 20: Van Buren's schools, desegregating under federal court order, report that they expect 23 black students.

Aug. 22: Georgia Gov. Marvin Griffin is roundly applauded when he tells a dinner meeting of 350 members of the Little Rock Capital Citizens Council that he will fight to maintain school segregation in his state. Griffin spends the night at the Governor's Mansion and breakfasts with Faubus.

Aug. 23: Just after midnight, a rock is thrown through the picture window at the home of Daisy Bates and her husband, L.C. Bates, publisher and editor of the black Free Press newspaper. Daisy Bates tells police that a note tied to the rock said, "Stone this time. Dynamite next.''

Aug. 25: A cross 8 feet high is burned on the lawn of L.C. and Daisy Bates. A sign near the cross bears a white-lettered message: "Go back to Africa. KKK.''

Aug. 26: U.S. District Judge Ronald N. Davies arrives from Fargo, N.D., to handle Arkansas desegregation cases after the withdrawal of Judge John E. Miller.

Aug. 27: An anti-integration order is sought in a state Chancery Court suit filed by Mrs. Clyde Thomason, secretary of the recently formed Mothers League of Little Rock Central High School. The 250 people attending a Mothers League evening meeting petition Faubus "to prevent forcible integration of the Little Rock schools.''

Aug. 28: Faubus meets privately for more than an hour with Arthur Caldwell, an Arkansan in the U.S. Justice Department. Caldwell has been sent from Washington by Deputy Attorney General William P. Rogers in response to an Aug. 21 call from the governor inquiring what the federal government would do if violence broke out in Little Rock. Caldwell reports later that when he asked Faubus for evidence of impending violence to turn over to the FBI, the governor replied that his information was too vague to be of value to law officers. Faubus disputes Caldwell's account in his 1980 book, Down From the Hills.

Oct. 7: Faubus says that 101st Airborne Division troops patrolling Central High School have invaded the privacy of girls' dressing rooms. Presidential press secretary James C. Hagerty calls the charge "completely untrue and also completely vulgar."

Oct. 17: U.S. District Judge Ronald N. Davies dismisses a petition filed by an officer of the Mothers League of Central High School, which asked that a three-judge court be convened to order federal troops removed from the school.

Oct. 24: The nine black students enter Central High's front door for the first time without escort by federal troops.

Nov. 18: The last 101st Airborne Division troops depart Little Rock, leaving federalized National Guardsmen on duty at Central High, still under the overall command of the 101st's Gen. Edwin A. Walker.

Dec. 17: Black student Minnijean Brown dumps a bowl of chili on two of her white antagonists in the Central High cafeteria. She receives a six-day suspension.

The city suffered during the 1958-59 school year through a trauma that unquestionably had a wider and deeper impact on residents' lives than the state-federal confrontation of September 1957.

Under a state law passed at the instigation of Gov. Orval E. Faubus, Little Rock voters in September 1958 were given the stark choice of shutting down the city's four high schools as public institutions for the academic year ahead, or accepting racial integration of all the system's schools.

The vote -- 19,470 to 7,561 in favor of closing public high schools to avoid integration -- left several thousand local students and their families scrambling to find alternative schooling in what became known as the "Lost Year." Not until Aug. 12, 1959, did Little Rock high schools reopen.

1958

Feb. 6: Brown is suspended again after another racial altercation. Also suspended is a white student, Lester Judkins Jr., who is said to have poured soup on her in the cafeteria. Brown then reportedly called another antagonist, Frankie Ann Gregg, "petty white trash" – after which Gregg hit the black student with her purse.

Feb. 17: The Little Rock School Board expels Brown for the year. The Board also suspends three white Central students: Billy Ferguson, accused of having pushed black student Gloria Ray down a flight of stairs; and Howard Cooper and Sammie Dean Parker, for having worn "One Down, Eight to Go" badges referring to Brown's suspension.

Feb. 20: The School Board asks the U.S. District Court to allow delay of integration here until the U.S. Supreme Court's requirement that desegregation be accomplished "with all deliberate speed" is more fully defined.

March 4: Sammie Dean Parker appears on a 30-minute paid television program to be interviewed by attorney Amis Guthridge, a leader of the segregationist Capital Citizens Council. Parker says she was unjustly suspended as an example to other white students.

March 12: Parker's suspension is lifted after she promises in writing to abide by Central High's rules of conduct.

May 6: The Pulitzer Prize board announces that two of journalism's most prestigious awards are going to the Arkansas Gazette – one for Meritorious Public Service in covering the desegregation crisis, the other to Executive Editor Harry S. Ashmore for his Editorial Writing on the subject.

A third Pulitzer Prize for stories about Central High goes to Relman Morin of the Associated Press, in the National Reporting category.

May 25: After a baccalaureate service honoring Central High's graduating seniors, a member of the senior class, Curtis E. Stover, jumps from a ledge and spits in the face of a black girl. Stover is charged with disturbing the peace.

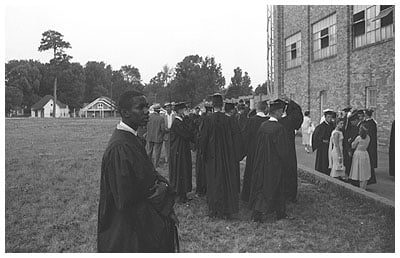

May 27: Ernest Green becomes the first black to graduate from Central High, joining 601 white senior classmates in commencement ceremonies at Quigley Stadium.

June 21: U.S. District Judge Harry Lemley, who has replaced Judge Ronald N. Davies in the case, grants a delay in Little Rock school integration until January 1961. Blacks have a constitutional right to attend white schools, but the School Board has shown convincingly that the time to exercise that right has not come, Lemley rules. "The personal and immediate interests of the Negro students must yield temporarily to the larger interests of both races," he writes, based on conditions in the community and the schools.

July 7: A bomb explodes on the lawn of black activists L.C. and Daisy Bates, leaving a deep crater and damaging their house.

July 29: Faubus wins the Democratic gubernatorial primary with 69 percent of the vote against two opponents.

Aug. 18: Acting on an appeal from the NAACP, the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in St. Louis reverses Judge Lemley's integration delay order in a 6-1 decision.

Aug. 25: The U.S. Supreme Court announces it will convene in extraordinary session Aug. 28 to take up the Little Rock school desegregation case. It will be only the fifth off-season term in four decades for the high court.

Aug. 26: Faubus addresses a special session of the state Legislature that he has called to recommend passage of six segregation bills.

Aug. 28: The Legislature passes the six anti-integration measures proposed by the governor. The favorable votes are unanimous in the Senate, with one to three opposing votes in the House. State Rep. Ray S. Smith Jr. of Garland County casts the only vote against the key bill authorizing the closing of schools.

Sept. 1: Awaiting the expected decision of the U.S. Supreme Court, the Little Rock School Board postpones opening of the city's four high schools until Sept. 15. Elementary and junior high schools are to open Sept. 4.

Sept. 12: In Cooper vs. Aaron, the U.S. Supreme Court rules unanimously in a six-paragraph decision that integration must proceed immediately at Central High.

After the ruling, the Little Rock School Board announces that high schools will admit students of both races when they open Sept. 15. Faubus then signs into law the acts recently passed by the state Legislature empowering him to close the schools temporarily pending a special election within 30 days at which Little Rock will vote "for or against the proposition of racial integration of all schools within the school district."

The governor next signs a proclamation closing Little Rock's four public high schools, "in order to avoid the impending violence and disorder which would occur and to preserve the peace of the community." He sets the special school election for Oct. 7.

Sept. 15: Superintendent Virgil T. Blossom says the Little Rock School Board has canceled football and all other extracurricular activities at the city's four high schools.

Sept. 16: Faubus advances the date of the special school election on integration to Sept. 27, saying he wants to get the issue resolved so classes can resume.

Fifty-eight white women, organized as the Women's Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools, meet under the aegis of Adolphine Fletcher Terry. Their initial statement, released the next day, urges Little Rock residents to vote for racial integration Sept. 27. There is "no other way to open our schools," declares the group.

Sept. 17: The Little Rock Private School Corp. is set up with the aim of leasing the four public high schools if taxpayers vote Sept. 27 to keep the schools segregated. Its president is Dr. T.J. Raney, a surgeon who is Faubus' personal physician and a member of a prominent local family.

The Little Rock School Board reverses itself and orders resumption of high-school extracurricular activities.

Sept. 19: About 65 white Hall High students meet and issue a statement calling for immediate opening of their school even if it means admitting blacks. Asked for his reaction, Faubus says 65 "doesn't seem like very many to me."

Sept. 22: Sixty-three Little Rock lawyers sign an advertisement in the Gazette and the Democrat stating their opinion that "existing public school facilities of this district cannot be legally operated with any public funds as segregated private schools."

Some 200 students from Central High demonstrate on the lawn of the Governor's Mansion against any integration of their school.

The first day of two-hour television classes for Little Rock high schoolers is deemed a success by most participants.

Sept. 27: Seventy-two percent of those casting ballots in the special Little Rock School District election vote "against racial integration in all schools" in the district. The vote of 19,470 to 7,561 means that the city's four high schools cannot open as public institutions with any blacks in attendance.

Four hours after the polls close, School Board President Wayne Upton announces that negotiations are under way to lease the high school properties to the Little Rock Private School Corp.

Sept. 29: The School Board leases the city's four high schools to the Little Rock Private School Corp. A few hours later, two judges of the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, sitting in Omaha, Neb., restrain the School Board from turning over the schools to the private body.

The U.S. Supreme Court, in a 17-page clarifying opinion on Cooper vs. Aaron, declares the Supreme Court's 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education ruling "the supreme law of the land" and forbids "evasive schemes for segregation."

Oct. 16: The Little Rock Private School Corp. announces that registration for seniors will begin Oct. 20 at its Raney High School in the former University of Arkansas Graduate Center at 16th and Lewis streets. Operating without public funds or public buildings, Raney High will attract about 750 white students. Another new privately operated facility, Baptist High School, enrolls about 300 students for classes at 2nd Baptist Church, 8th and Scott streets.

The rest of the city's 3,698 high schoolers and their parents have to make other arrangements for the 1958-59 academic year. Many students attend school elsewhere in Arkansas or out of state while living with relatives or friends.

Nov. 4: Faubus is elected to his third two-year term as governor, garnering 83 percent of the vote against Republican George W. Johnson.

Segregationist write-in candidate Dale Alford, an ophthalmologist and Little Rock School Board member, defeats eight-term incumbent Rep. Brooks Hays by 30,739 to 29,483 for the 5th District seat in Congress. Hays has come to be seen as a racial moderate since September 1957. Alford resigns from the School Board after his election victory.

Ardent segregationist Jim Johnson, whom Faubus had defeated in the 1956 gubernatorial primary, is elected to the Arkansas Supreme Court.

Nov. 12: The five remaining Little Rock School Board members resign in frustration at the integration impasse. They quit after buying up the remainder of Blossom's contract (through June 30, 1960) and agreeing to pay him the $19,741 due at his superintendent's salary of $1,100 a month.

Dec. 6: Voters choose a new School Board. It proves to be evenly divided on desegregation. Elected are three candidates of the so-called businessmen's slate -- Everett Tucker, Russell Matson and Ted Lamb -- who favor compliance with the federal courts. Two of the other winners -- Ben Rowland and R.W. (Bob) Laster -- espouse continued resistance to federal integration orders. The sixth member, Ed I. McKinley, is elected unopposed with the support of both sides but turns out to be a Faubus supporter.

Dec. 28: The Gallup Poll's annual list of "The Ten Men in the World Most Admired by Americans" ranks Faubus in the No. 10 spot. President Dwight D. Eisenhower is No. 1. In his 1980 book, Down From the Hills, Faubus asserts, "No other governor had ever made the list."

1959

March 2: The Little Rock Chamber of Commerce announces its members have voted 819-245 for reopening the city's high schools "on a controlled plan of minimum desegregation acceptable to the federal courts."

May 5: The three pro-segregation members of the School Board fire 44 teachers and administrators they consider supporters of integration. They also appoint as school superintendent T.H. Alford, father of Dale Alford. The other three members of the board have walked out of the meeting beforehand.

May 8: STOP (Stop This Outrageous Purge) is formed to seek an election recall of the School Board's three segregationist members. Some 179 Little Rock residents, including civic leaders, attend STOP's organizational meeting at the Union Bank Building. The Women's Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools begins working closely with STOP.

May 16: In response, segregationists organize CROSS (Committee to Retain Our Segregated Schools) to recall the other three board members, who favor acceptance of integration. The initial CROSS rally draws 350 people to the Marion Hotel.

May 25: STOP forces prevail in the recall vote by a narrow margin. With about 25,000 votes cast, the three STOP-backed School Board members are retained by margins ranging from 50.8 percent to 52.4 percent. The three pro-segregation members are removed by percentages ranging from 52.9 to 55.5.

June 11: The Pulaski County Board of Education appoints three new Little Rock School Board members to replace those recalled by voters. The new members are state Rep. J.H. Cottrell Jr., contractor Henry Lee Hubbard and insurance company official B. Frank Mackey. The reconstituted Board rehires 39 of the 44 employees fired on May 5.

June 18: A three-judge U.S. District Court declares the state's 1958 school-closing law unconstitutional. The Little Rock School Board announces that it will not appeal the decision and will reopen the city's high schools in the fall.

July 21: Baptist High's Board closes the school after one year, citing a lack of students.

July 31: Three black students are assigned to Central High and three to Hall High for the 1958-59 school year. No blacks are assigned to Technical High, and no whites are assigned to Horace Mann, the city's black high school.

Aug. 4: The Little Rock School Board unexpectedly announces that classes will begin Aug. 12, nearly a month earlier than scheduled.

Officials of privately operated Raney High announce that the school will close because it is out of money.

Aug. 11: Faubus goes on television to discourage overt resistance when high schools reopen. "I see nothing to be gained tomorrow by disorder and violence," says the governor. Instead, he urges viewers to "go to work and elect some officials who will represent you and not betray you." He emphasizes that he is "not throwing in the sponge."

Aug. 12: Little Rock's four high schools open. Three blacks -- Effie Jones, Estella Thompson and Elsie Marie Robinson -- enroll at Hall. Two of the original "Little Rock Nine" -- Jefferson Thomas and Elizabeth Eckford -- enroll at Central. Eckford finds out that she has enough correspondence-school credits for her degree and doesn't need to continue classes. Another "Little Rock Nine" student, Carlotta Walls, enrolls at Central later in the month.

After a morning segregationist rally at the state Capitol, where three arrests are made, some 250 demonstrators attempt to march on Central High. On the orders of Police Chief Eugene G. Smith, fire hoses are turned on the protesters after they try to break through police lines at 14th and Schiller streets, one block from the school. Twenty-one arrests are made. The crowd disperses.

Aug. 28: Two unidentified women throw two tear-gas bombs inside the front door of the school administration building while the Board is meeting on the second floor. There are no injuries.

Sept. 7: Three dynamite blasts shake the city on Labor Day, though nobody is hurt. One blast demolishes a city-owned station wagon parked in the driveway of Fire Chief Gann Nalley's home. Another damages the front of a two-story building housing a construction firm of which Mayor Werner Knoop is vice president. The third detonates at the school administration building, wrecking an empty office.

Sept. 9: Two Little Rock men -- lumber and roofing company owner E.A. Lauderdale and truck driver J.D. Sims -- are arrested in the bombings and charged with dynamiting a public building.

Sept. 10: Three more local men are arrested on the same charges. All five defendants are later convicted, fined $500 and sentenced to prison terms of three to five years. Testimony indicates that the mastermind of the attacks was Lauderdale, an active member of the Capital Citizens Council. Lauderdale's prison term is commuted by Faubus after a little more than five months.

Sept. 13: Faubus is in attendance as evangelist Billy Graham preaches for 45 minutes to an audience of 30,000 in the second of two revival meetings in War Memorial Stadium.

Graham refers to the desegregation crisis, declaring that "only Christ can heal these scars and wounds." About 600 people come forward in response to Graham's regular call for public witness. He challenges the news media "to carry this story of hundreds of people of both races standing at the foot of the cross to receive Christ." |